Faces of Title IX: Women share their stories

Published 2:53 pm Monday, July 14, 2014

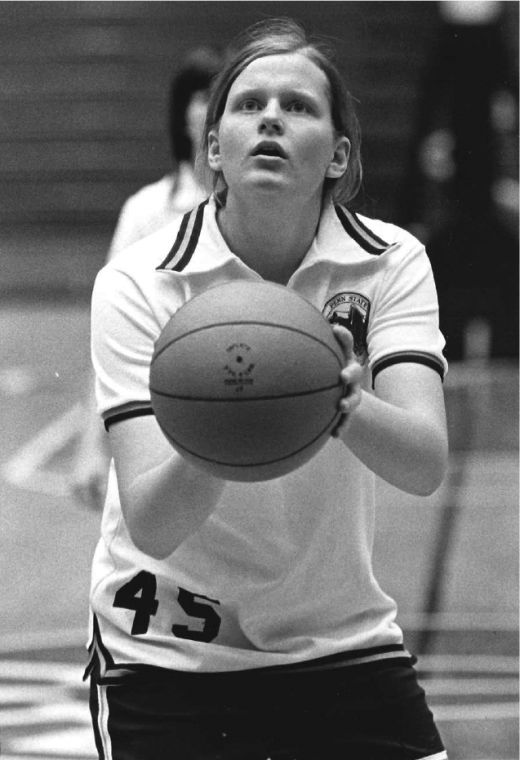

- Mag Strittmatter played basketball against her brothers and their friends before her high school formed a girl's team. She was one of the first members of the Penn State's women's basketball team.

An Olympic-level diver, a high school valedictorian looking for big-city adventure, a softball player who refused to quit and a basketball star who learned the game by playing against her brothers’ friends. All were pioneers in women’s college sports when Title IX equalized access to academics and athletics.

Here are their stories.

Laura Silvieus, University of Chicago

ASHTABULA, Ohio – Laura Silvieus may not call herself a pioneer, but 40 years ago she stood where few women America had ever been – at the threshold of college with an athletic scholarship.

“I didn’t knock down any barriers,” said Silvieus. “I just happened to be there when doors opened.”

Silvieus didn’t need much help getting into college when she graduated as valedictorian from Edgewood High School near Ashtabua. She led the student council and her senior class. She was vice president of the science club. She captained the girls’ softball and basketball teams and was MVP in a recreational volleyball league.

“I would have gone to college whether I got a scholarship or not,” she said.

But shortly after the passage of Title IX, an English teacher showed Silvieus a Parade magazine article about the University of Chicago’s offer of athletic scholarships to women. One student was to receive a scholarship for the 1973-74 school year. Interest was so overwhelming that two awards were given, to Silvieus and Noel Bairey of Modesto, Calif.

Silvieus said the University of Chicago, 400 miles from home, gave her a big-city education while making graduate school attainable. Chicago also was the setting of a successful athletic career: Silvieus was MVP in volleyball in 1975 and 1976, and in basketball in 1977. She wrote her name into the university’s record book and was inducted in the inaugural class of its athletic Hall of Fame in 2003.

Athletics also gave her – and her teammates – confidence.

“It gave us the confidence we could do anything we wanted to in the world,” she said. “… It wasn’t that we felt we were going to take on the best male athletes and win, but we could take on people our size and do quite well.”

Silvieus wasn’t the only member of her family to benefit from changes spurred by Title IX. Her younger sister, Lynne, attended Ohio Northern University on athletic scholarship.

Neither could have afforded the colleges they chose without the scholarships, said Jackie Hillyer, who coached them at Edgewood.

“That’s where you see the advancement of Title IX,” said Hillyer. “It opened up the ability for girls to go to colleges they wouldn’t have otherwise had the chance to go.”

Silvieus is now semi-retired from managing a law firm in Oakland, Calif. She plays golf, snowshoes and goes backpacking, but she doesn’t actively compete.

Silvieus, who has no children, sometimes talks to her nieces and other younger girls about athletics and Title IX, she said, “but never as a life lesson. It’s hard for them to really understand the concept that sports were not available. There’s no need to go to the past.”

— Bob Ettinger / Ashtabula, Ohio, Star Beacon

Megan Neyer

ASHLAND, Ky. — Title IX helped Megan Neyer climb the diving platform en route to 15 national championships. But the landmark law’s greatest impact, said Neyer, is not measured in individual efforts as much as it is in creating teams.

An Ashland native, Neyer competed on a championship swimming and diving team in high school. She and swimming star Tracy Caulkins were freshman roommates at the University of Florida and together led the Gators to the inaugural NCAA women’s swimming and diving championship in 1982. Many more titles would follow.

Neyer was an eight-time Southeastern Conference and NCAA champion — a feat not accomplished before or since — and maintained a 3.5 grade point average. She won the U.S. Olympic trials in springboard and platform diving in 1980 but didn’t compete because the United States boycotted the Moscow Olympics.

Neyer said she “absolutely” benefited from Title IX and recalled the inequality of the men’s and women’s teams at Florida. “Through my years in college we weren’t getting the equivalent ceremonial kinds of things, like rings and watches,” she said.

But the law’s most significant impact, she said, is creating opportunities for women to compete on teams. Athletes learn to collaborate and communicate – skills that transfer to the workplace.

Neyer said engaging more people in athletics, especially children, also will help address the obesity crisis. She recently began a program at a parochial school outside Decatur, Ga., designed by U.S. Olympians to end childhood obesity. The program aims to get middle school-aged children exercising 45 minutes per day for 40 days.

“I worry about this next generation of kids, spending more and more time in front of a computer instead of out on a soccer field,” she said.

Neyer retired from competitive diving in 1988. She returned to graduate school at Florida to complete her master’s degree in sports psychology in 1990 and her doctorate in counseling four years later. She’s a member of the University of Florida and International Swimming halls of fame.

She is now president of Neyer Performance Strategies, a Georgia-based company that works to enhance individual and team performance in business and athletics. Neyer has worked with executives, coaches and athletes for 20 years.

— Rocky Stanley / The Ashland, Ky., Independent

Mag Strittmatter, Pennsylvania State University

JOHNSTOWN, Pa. – Mag Strittmatter probably never will forget the day the girls at Cambria Heights High School gathered in the auditorium for an important announcement: A girls’ basketball team was forming.

“I felt like I had hit the lottery,” she said.

Strittmatter had spent countless hours playing basketball against her brothers, John and Bob, in the family barn. “When their friends come over, it was a great chance to learn how to play,” she said.

She eventually took her basketball skills to Penn State University, where she was among the first women to receive an athletic scholarship. She made the most of the opportunity and led the Nittany Lions in rebounding in all four years of her career. Her average of 10.3 rebounds a game is still the best in Penn State history.

Strittmatter, 55, now director of an organization that helps low-income people in Denver, said Title IX “changed my life in ways I never could have imagined.”

“Our family was not one of much means,” she said. ”To have the opportunity to go and play in college and earn an athletic scholarship was an incredible opportunity for me and a great blessing for our family.”

Cambria Heights’ Lady Highlanders formed the year before President Nixon signed Title IX into law. The team wore modified gym uniforms with numbers tied around their waists. That didn’t dampen the experience for Strittmatter, who averaged 27 points per game during three seasons.

After graduation, Strittmatter briefly worked at a sewing factory to save money to attend Penn State’s campus in Altoona. Her plans changed when Penn State’s new women’s basketball coach, Pat Meiser, invited her to try out.

Meiser’s job was to build a program, said Strittmatter, and make “what was the equivalent of a club team into a college team.” Strittmatter led Penn State with 18.3 points as a freshman in 1974-75. Her 260 rebounds three years later set a single-season record.

Strittmatter said playing for Penn State taught her to be competitive and challenge herself.

“In those days, female athletes were not considered on the same level as male athletes. You had to work really hard. You had to study. You had to work on the sport that was your job,” she said. “It taught me a lot about responsibility. It helped me grow up.”

— Mike Mastovich / Johnstown, Pa., Tribune-Democrat

Shirley Webster, Oklahoma State University

STILLWATER, Okla. — Shirley Webster and her teammates were not aware of the financial implications of Title IX for Oklahoma State University. “We just wanted to play,” she said.

Webster was involved in several sports – including volleyball, field hockey and competitive badminton – when she and others organized Oklahoma State’s first softball team.

The university tried to stop the program, she said.

“They kept flinging things at us, and I think they thought it would make us go away,” she said. “And their final attempt was, ‘Well, even if you have a team, you don’t have a coach, and we can’t afford to pay anybody.’ But we had already talked to (Coach Pauline Winters) and we got it going.”

Webster said the success of Oklahoma State’s women’s softball team over the past 40 years later makes her proud. Last year, the Cowgirls reached the Women’s College World Series.

“We had no idea when it first got started just what type of opportunities would grow for women now,” she said. “It’s just awesome.”

Webster continues to see changes in gender equality in sports. She works as a middle school and high school coach in Oklahoma City.

“Sports are just such an accepted part of their lives. It’s not like the male athletes look at the female athletes any differently,” said Webster, who coaches volleyball and slow-pitch softball. “We are all now in the same club.”

— Jason Elmquist / Stillwater, Okla., NewsPress