Murders bruise small Georgia town’s football champions

Published 3:00 pm Friday, March 25, 2016

- Organizers of a recent Stop the Violence march and rally in Moultrie, Georgia say more than 500 people participated.

MOULTRIE, Ga. — Tykerious Jones seemed destined to become the next star running back for the Colquitt County Packers, one of the most successful high school football programs in Georgia.

Jones never took a single handoff in a game last year.

Just weeks before the start of the season, the rising junior was charged with murder in connection with the shooting death of 68-year-old John Hester Sr. Two former players were also charged.

Eight months later, Jaquan Willis became the second Colquitt County football player to be charged with murder. He is accused in the shooting death of a 33-year-old mother, Fatisha Clark, at a city park early this month.

The charges against Jones and Willis have brought scrutiny to a team that just clinched back-to-back state championships and ended last season atop two national polls.

But school officials and community leaders say there are limits to what the football team or its coaches, even with a dominant role in players’ lives, can do to prevent such tragedies while confronting the effects of poverty and, lately, simmering gang activity.

They also point to the team’s successes in molding its young players, including dozens who’ve received scholarships and likely could not have afforded college without assistance.

“We’ve lost some battles, but we’re winning the war,” said the Packers’ head coach, Rush Propst, in an interview.

“Churches, parents, the school system and our football program — everybody has lost that battle. But in the whole wage of war on crime and changing a culture and trying to better a life for a child, I think we’re winning the war,” he said.

Superintendent Samuel DePaul said the schools are doing all they can to catch students who may be slipping away. Social workers and counselors step in when students are identified as needing help.

Asked how the schools are addressing the fatal shootings, he said, “We’re working hard to do the best we can every day — that’s what we’re doing.”

“There could be another one tonight,” he said. “We don’t have control over those kinds of things that occur.”

However, the shootings have left Propst wondering what signs he may have missed that his players were headed toward trouble.

Two shootings, two players

Propst said Jones’ arrest last July, in particular, caught him unaware.

The polite and hard-working 17-year-old known as “Grump,” who had already caught the eye of Division 1 colleges, was “less than a month away from being in a safe house,” Propst said, referring to the start of football season.

There would not have been any time — or energy — for trouble once the season was underway, he said.

Both shootings took place in the offseason.

Last summer’s occurred when Hester confronted teens whom investigators said planned to rob the home of Hester’s son. Police said Hester was shot with a firearm stolen from an earlier burglary.

Jones was not identified as the triggerman. He was one of seven teens charged in connection with the case. Five have since pleaded guilty to planning to commit home invasion, in exchange for having the murder charges against them dropped.

Jones’ father, Trabian Jones, said his son deserves to pay for his involvement in the burglary, but he will contest the other charges.

His son had no control over the shooter’s decision to fire at Hester, he said. Trabian Jones also questioned why Hester — armed with a shotgun — intervened in the apparent robbery instead of calling the police. Investigators believe Hester fired several shots.

“It’s going to take 12 people to send him to prison,” Trabian Jones said in an interview Tuesday.

Jones’ attorney, a public defender, said he does not comment on pending cases.

Trabian Jones said his son — who would come home from practice, shower and pass out – dreamed of playing football at the University of Georgia.

Now, he awaits trial in a jail cell.

A barber in Moultrie, Trabian Jones said he believes boredom and hanging with the wrong people led his son to trouble.

“You can talk to your child until you’re blue in the face, but once they get out of your presence, the choices that they make are their own choices,” he said.

As for Willis, Propst said a leg injury benched the sophomore most of last season.

“I believe the idle time is what ate him up,” he said. Propst described the 16-year-old as a fourth-string running back on the team.

Contacted through his attorney, Willis and his family declined to comment for this story.

Propst said the shootings will make him “more attentive” to players in need. He thinks the schools should hire a social worker and pay a psychologist to work with players, as well.

Jones lost two close family members — including his grandmother — in a car wreck in late 2014.

Willis’ father is in federal prison, according to court records.

Many members of the Packers confront similarly difficult family situations. Going through his roster of about 125 kids, the coach identified many players from a one-parent home or who live with a relative.

Propst talked about players who lack life’s essentials, such as regular meals and a bed, and who have lived with coaches or with others in the community.

The coach was nationally known when he arrived in Colquitt County in 2008, having playing a central role in an MTV reality show called “Two-a-Days” that followed the high school team in Hoover, Alabama, while he was its coach.

He now is outspoken about the football team’s role in saving young men who may otherwise go down the wrong path.

He told state lawmakers earlier this month that the program is a tool to change lives. That was the day the Packers were honored as state champions in Atlanta — just four days before the shooting at the park.

In an interview after the shooting, Propst elaborated, “This is not a football problem. It’s a society problem, it’s a cultural problem, and it’s a problem that I think athletics helps or it would be — in my opinion — 10 times worse.”

‘Heavy search for gangs’

Colquitt County is among Georgia’s poorer communities. A quarter of all residents — and nearly 40 percent of those under age 18 — live in poverty.

This southwest Georgia community, home to about 46,000 people, is best known for its vegetables, farming, chicken plants and — for the last several years — high school football. It seems like the last place that might harbor gangs.

But, as Georgia Bureau of Investigation agents have looked into recent murders in Moultrie, they’ve found information suggesting gang activity, said Bahan Rich, assistant special agent in charge in the GBI’s Thomasville office.

Two in particular — the Bloods and Gangster Disciples — are the gangs most commonly mentioned, he said.

“However, the murders that we have assisted the Moultrie Police Department with do not seem to be a result of the gang activity,” he said.

Propst said he worries about the influence of gangs seeping into his team, leading him to chase down any rumor about a player who may be involved.

He’s never had proof, he said.

“If they’re a member of a gang, and I can pin it on them, they will not be a member of this football team,” he said. “I will cut them loose so fast that it’ll make your head spin. I’m not going to put up with it.”

This month’s shooting, in particular, elevated concerns in the community about gang activity.

It was a sunny Sunday afternoon — the kind of early spring day that draws people out of their homes — when gunshots rang out in Northwest Moultrie.

Children were running around a playground, and teens were playing basketball nearby when a fight escalated into public violence.

Willis is accused of firing six shots from a moving car. One of them struck Clark in the stomach as she visited the park with two of her three children.

George Wallace, who once coached Willis, said he still struggles to believe the teenager could have anything to do with it. He described Willis as a good kid from a respected family.

It’s the kind of fate that Wallace had hoped to help kids avoid when he brought a Pop Warner football team, called the South Georgia Hawgs, to the area.

He said he realized that sports can only do so much. Eventually, games are over and seasons end.

“You can’t protect them all,” he said.

Kids need more than athletics, Wallace said. They need what he calls “hard love” and a deeper connection with adults who can be mentors.

Wallace, who helped start an anti-gang program called Boys to Men, said he thinks — or at least hopes — Moultrie’s gangs are a fad.

“To them, it’s cool,” he said. “And it’s just destroying lives. It’s actually destroying the fabric of the community.”

The murders have renewed calls to curb violence. A parade of people — including Propst — marched through Northwest Moultrie last weekend to bring attention to the problem.

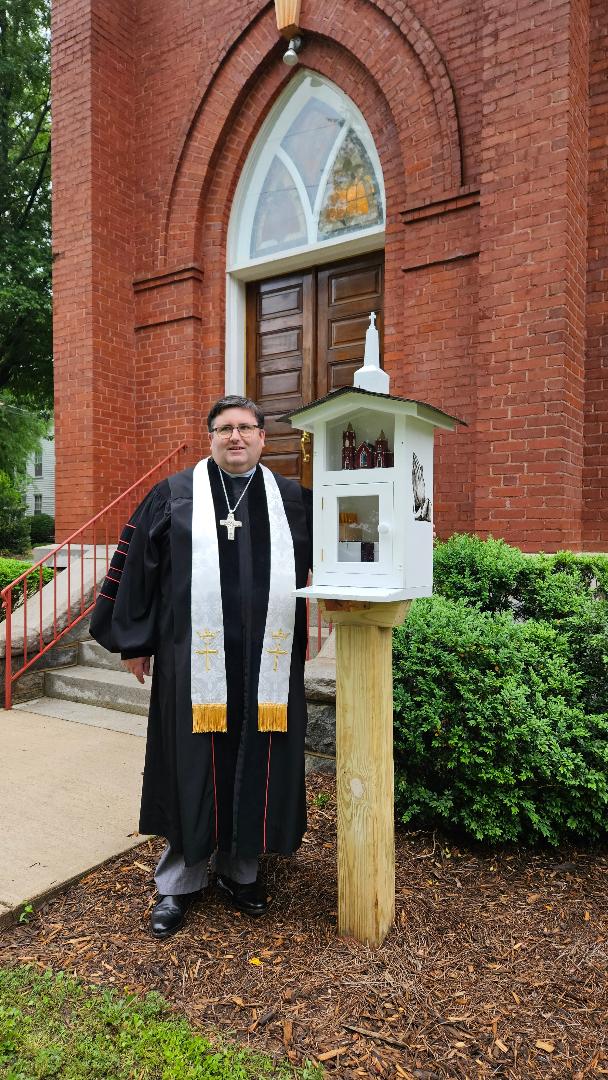

“If we’re not able to grab hold of it now, then it will grow and be out of control,” said the Rev. Travis Williams, pastor of New Beginning Bible Church, near where the shooting of Clark occurred.

Higher ground

For many players, football represents a way to overcome the potential dangers of gangs and generational poverty, Propst said. In many cases, it’s a chance to become the first in their families to attend college.

When talking to players, Propst said he tells them to leave Moultrie after high school to attend college or join the military.

The ones who stay, he said, tend to struggle to earn a living — or worse.

Football, he said, can “push these kids to higher ground.”

That’s why Propst says he’s most proud of those players who have received scholarships — 94 in the eight years that he’s been head coach.

A scholarship doesn’t always come with a happy ending, though.

One recipient, Nyneson Jeudy, was arrested shortly before leaving for Kilgore College, a junior college in Texas. Propst said he still communicates with Jeudy, who is now in prison.

Then again, Jimmy Jeter, a civic leader in Moultrie, recalled the story of R.J. Taylor, one of the first Colquitt County football players under Propst to win a scholarship.

He played on the offensive line at Henderson State University in Arkansas, where he majored in finance. He now works as a financial advisor in Atlanta, Jeter said.

“We don’t want to lose sight of all the good stories because of a couple that foul up and make horrible, horrendous decisions,” he said.

Still, Jeter said the recent shootings have left the community with “extreme disappointment.”

“Not because we’ve lost a football player, but because we saw a young child or young adult who squandered a great opportunity to better themselves,” he said.

The Rev. Cornelius Ponder said the football team — which saw two-dozen players sign last month to play in college — helps foster an “inner hope” for young men in the community.

Like Propst, he said more youth would find themselves in trouble without it.

Still, “inner pride” can cause young men to cave to peer pressure, said Ponder, who manages the Groveland Community Center, which houses the Boys to Men program. They need an environment beyond the gridiron that provides “genuine nourishment” to help overcome those pressures.

That’s why he and others want this community to rally around its youth with the same energy it brings to Mack Tharpe Stadium on Friday nights.

“Just like how we win championships in football, we are going to win some championships in morals, values and enriching our children’s lives,” he said.

Jill Nolin covers the Georgia Statehouse for CNHI’s newspapers and websites. Reach her at jnolin@cnhi.com.