Questions remain about effectiveness of legal reforms following Sandusky sexual abuse scandal

Published 12:47 pm Sunday, April 9, 2017

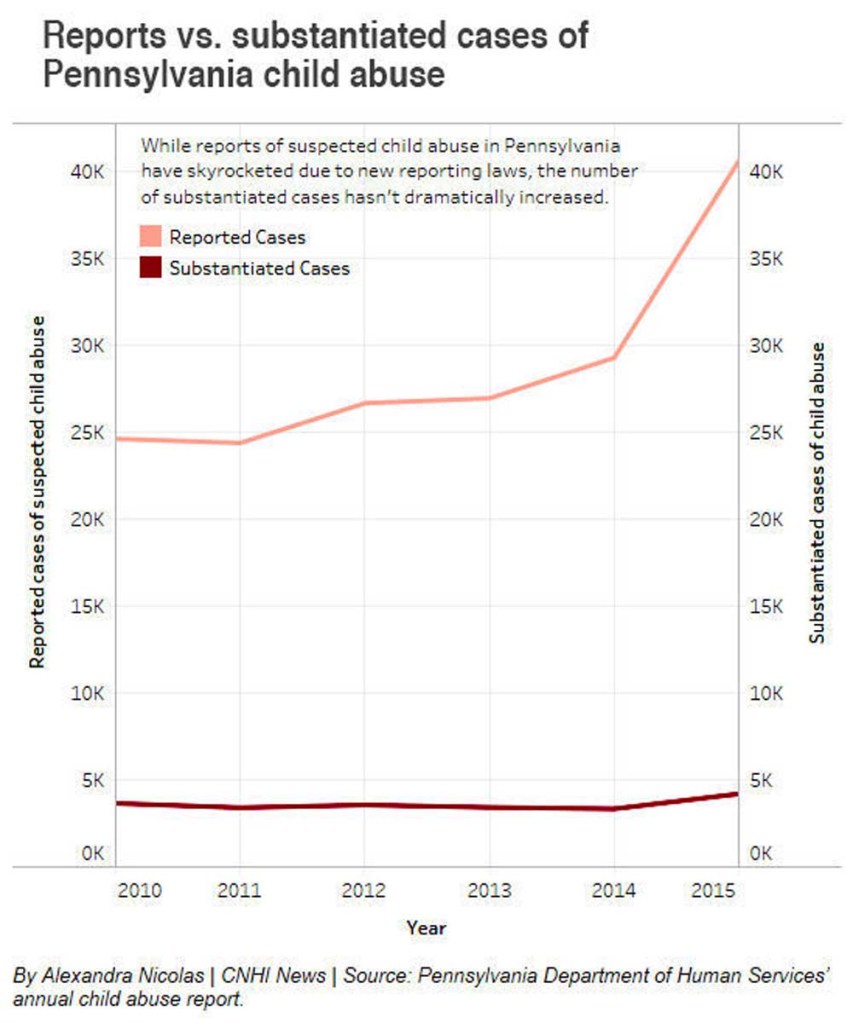

- GRAPH: Reports vs. Substantiated cases of Pennsylvania child abuse

HARRISBURG, Pa. — More than two dozen Pennsylvania child protection bills created in response to the Jerry Sandusky sex abuse scandal have made more work for caseworkers, but no one’s sure they’ve made children much safer.

The arrest and conviction of the former Pennsylvania State University assistant football coach for more than 40 counts of sexual abuse of children — along with revelations about the cover-up at the university prior to his arrest — spurred the state to create a task force to examine whether Pennsylvania’s child protection laws needed to be beefed up.

The group’s work led to changes requiring vastly more people to report suspicions of child abuse and changed the state’s definition to make it easier for caseworkers to substantiate abuse.

And in a move that directly strikes at the dynamic at play at Penn State, the law was changed so that professionals involved with children must report suspected abuse themselves rather than notify their bosses.

In some ways, it’s worked.

“If the measure is, did we get more reports, that’s a success,” said Cathleen Palm, founder of the Center for Children’s Justice. “We got a boatload of reports.

In other ways, advocates and those close to the system say, they may be swamping caseworkers so it’s harder to focus on cases of actual abuse in the midst of the avalanche of allegations.

“We have to stop deluding ourselves that the hard work is making the report” of suspected abuse, Palm said. “The system is overwhelmed.”

Here are the key findings based on state data and interviews with advocates and elected officials:

• The number of reports of suspected child abuse increased 65 percent from 2010 to 2015, according to state data. The number of substantiated cases of child abuse increased as well, but at 15 percent it was not nearly as drastic an increase, raising concerns that swamped caseworkers are either chasing unfounded reports or failing to document cases of actual abuse.

In 2010, 1 in 7 of the 24,615 reports of suspected child abuse was substantiated. By 2015, as the number of reports spiked to 40,590, the rate had dropped to 1 in 10.

• While the number of cases of suspected child abuse increased dramatically, spending on child protection didn’t.

Spending on child abuse investigations increased just 6 percent from 2010 to 2015, state data reveals.

A big reason is that counties must demonstrate the need for funding and they couldn’t document that need ahead of time. In 2009-10 Pennsylvania’s county child protection agencies spent just under $43 million investigating possible child abuse. By 2014-15 after the number of allegations spiked, spending only increased to $43.5 million, according to state data.

Spending is starting to pick up, but in a time when the state is dealing with a $3 billion budget shortfall, advocates warn it may not be enough to make up the lost ground.

• Because of problems in four of the state’s most populous counties, 1 in 5 children in Pennsylvania live in a county where the state has issued a warning about shortcomings in the county child protection system within the past two years.

Two Pennsylvania counties – Philadelphia and Luzerne – have child protection systems operating under provisional licenses, according to the state Department of Human Services.

That means the state has documented serious shortcomings in the way they are operating.

The state handed out the same warning last year to the child protection agencies in York and Dauphin counties. The shortcomings in York and Dauphin were documented by Auditor General Eugene DePasquale. He has launched a statewide review to determine if there are systemic problems.

• The number of babies born addicted to drugs increased 82 percent from 2010 to 2014, based on cases involving mothers enrolled in Medicaid, according to an analysis by the Center for Children’s Justice.

In 2014, the group identified 1,970 cases of babies who had been exposed to drugs during pregnancy. That’s more than five babies a day diagnosed with Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome and the numbers represent an incomplete picture because they don’t include children born to mothers who had private insurance.

Advocates with the group say their efforts to get clearer data have been stymied by the fact that while hospitals must report to counties when babies are born addicted to drugs, the counties don’t keep data on how often they received these notices.

These issues have largely fallen off the radar since the child protection reforms of 2013 and 2014, advocates say.

Struggling to keep up

In 2015, 34 children were killed by abuse or neglect, said Angela Liddle, president and CEO of the Pennsylvania Family Support Alliance.

With the crush of additional work, the people hired to intervene to help those kids in danger “are struggling to keep up. They have high turnover and the average caseworker only has two years experience,” Liddle said. “They’ve had to do yeoman’s work with not enough resources.”

Liddle and other advocates are dismayed there isn’t more urgency to fix the problem.

“You are hard-pressed to find a champion,” Palm said.

That changed in February when DePasquale waved a red flag after his audits of the child protection systems in York and Dauphin counties.

DePasquale said the issue got on his radar when his auditors examined the problems with the ChildLine hotline.

One of the surprises of that review was the Department of Human Services had told lawmakers that they thought the law changes could be handled without the Legislature allocating new money.

“They were on record as saying they didn’t think it was going to change much,” he said.

“I don’t know how you could reach that conclusion.”

At that time, he told his staff to take a closer look at how the law changes were affecting the county child protection agencies. They found alarming problems in Dauphin and York counties, two of the counties that had been given provisional licenses by the state.

Concerned that the problems might be more widespread, DePasquale has launched a statewide review focusing on 13 counties to try to gauge the breadth of the crisis.

More changes needed

The auditor general isn’t entirely alone in trying to draw attention to the issue.

State Rep. Katharine Watson, R-Bucks, is chairwoman of the House committee on child welfare. She shepherded the original bunch of child protection bills through the Legislature and she’s now trying to get momentum to take a similar examination of the impact of the state’s heroin epidemic on children.

The drug crisis, coupled with the increased work for caseworkers created by the child protection law changes, created “a perfect storm” hitting the state and county agencies charged with responding to abuse allegations, she said.

The challenges were magnified by the fact that the state had no mechanism for counties to seek additional funding in anticipation of a spike of reports, said Brian Bornman, executive director of the Pennsylvania Children and Youth Administrators, the trade group representing the officials who head county child protection agencies.

“Everyone could see the handwriting on the wall, but there was an unwillingness” to front-load additional funding.

Making matters worse, the state’s child abuse hotline doesn’t screen calls. It just forwards them to the county. Caseworkers may be spending too much time filling out paperwork to close cases that aren’t going to lead to findings of abuse.

“There is no means to pull the plug” on cases that are obviously not abuse, he said.

Bornman said that because counties now have been dealing with the increase in abuse allegations for a couple years, they are better able to demonstrate their need in their budget requests to the state. As a result, in the coming year, the funding should start to catch up with that need, he said.

But that doesn’t mean the staffing concerns are fading entirely.

Child protection is handed by the counties. Because of this, Watson worries that the level of care varies too much across the state. Part of this depends on how much of a priority the county commissioners make of it. Part of it depends on the pool of potential caseworkers that agencies have to draw from.

In more suburban areas, there may be more potential caseworkers for agencies to choose from. In rural parts of the state, there are counties where there aren’t enough qualified people.

“Your ZIP code should not determine the kind or level of service you get,” Watson said.

“I’m not sure anyone knows how to tackle it right out the gate,” Liddle said.

Many county child protection agencies are dealing with high turnover rates and many of the caseworkers on the job are young and inexperienced.

“You have kids right out of college who have never had kids themselves,” she said. “These people go into situations every bit as dangerous as those faced by law enforcement and they do it without weapons.”