Final plant closure marks end of coal-fired era in Massachusetts

Published 11:07 am Friday, June 2, 2017

- Energy production in New England

BOSTON – While the shutdown of the last coal-fired power plant in Massachusetts this week marked the end of the state’s decades-old reliance on the fossil fuel, the transition to other sources of energy creates myriad challenges.

Brayton Point Power Station in Somerset — the largest coal-fired plant in New England — went dark Wednesday as part of a shutdown that was underway for several years.

The 1,500-megawatt power plant was the last of the so-called “Filthy Five” dirtiest power generators. They included Salem Harbor Power Station, which stopped burning coal on June 1, 2014, and Mt. Tom power plant in Holyoke, which shut down a month later.

Environmentalists and health advocates this week heralded the end of the coal era in Massachusetts, saying it will help lower the region’s greenhouse gas emissions and accelerate the development of renewable energies such as wind and solar power.

“Coal is the past, clean energy is the future,” said Emily Norton, director of the Massachusetts Chapter of the Sierra Club. “We know that this transition is good for our health, good for our economy, and good for our kids as they graduate and seek stable, good-paying jobs.”

Jonathan Levy, a Boston University professor of environmental health, said the state has proven the shift away from coal can be made without raising electricity prices or hurting the economy.

“The reality is that the lights have stayed on in Massachusetts, even as these facilities have shut down or transitioned to other types of fuel,” he added.

Dan Dolan, president of the New England Power Generators Association, said stringent federal pollution regulations and the availability of cheap, domestic natural have paired to make coal-fired power plants too expensive to operate.

“Coal really hasn’t played a large role in the regional electric grid in years,” he said. “The energy market has already been phasing coal out, in part, because of the economics.”

He said state and federal environmental policies, as well as public opposition, make it unlikely that another coal-fired power plant would be approved in Massachusetts.

“It’s hard to see the state ever moving back in the direction of coal,” Dolan said.

Massachusetts has lowered its carbon emissions by 47 percent since 2005, partly because of the decline in coal use, according to the Georgetown Climate Center.

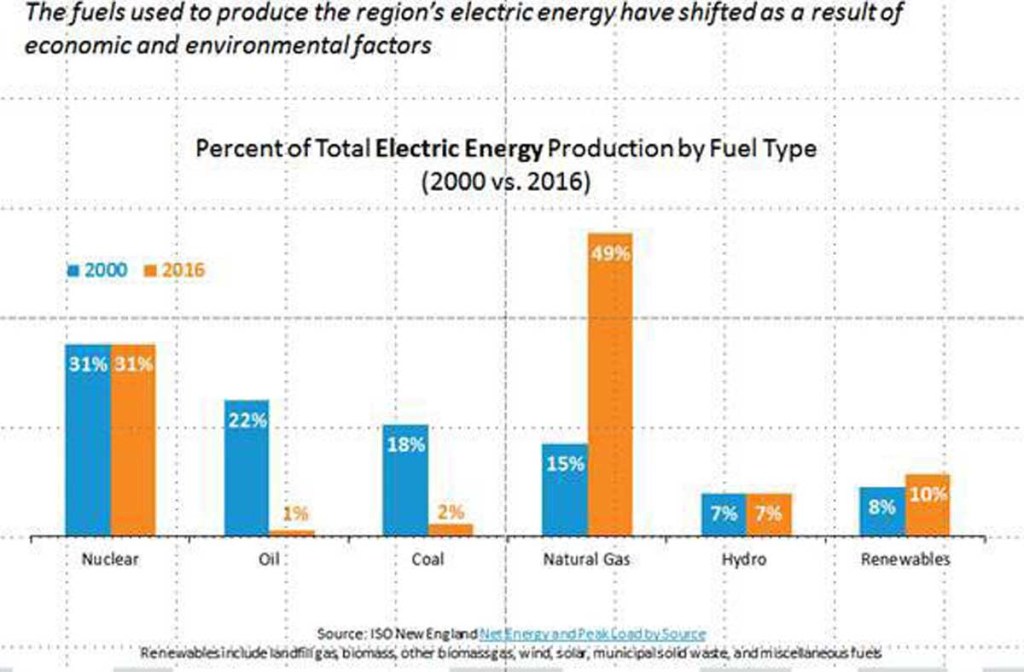

Two decades ago, about one-quarter of the electricity generated in the Bay State was produced by coal-fired power plants, according to the U.S. Energy Department.

Last year, coal accounted for only about 2 percent of the power generation — from Brayton Point and three other coal-fired power plants including two located in New Hampshire.

Nearly 50 percent of New England’s energy now comes from natural gas, while a third comes from nuclear power, according to ISO New England, the organization that oversees the regional power grid.

Hydropower, solar and other renewables accounted for about 15 percent of the energy sent to the regional grid, the group said, while only 1 percent comes from oil.

Massachusetts faces a looming energy crunch with an anticipated loss of more than 10,000 megawatts of power over the next few years as fossil-fueled plants are shut down. The Pilgrim nuclear plant in Plymouth is scheduled to go dark in two years.

Besides energy demand, the state is committed to cutting the state’s carbon output by 25 percent of 1990 levels within four years by tapping into renewables.

Last month, Gov. Charlie Baker signed a wide-reaching energy bill that requires utilities to pursue long-term contracts with hydropower suppliers and offshore wind developers.

The measure also requires that the state explore storage options for renewable energy.

Baker administration officials say solar and wind alone won’t can’t provide enough juice to meet energy demands, and that gas and hydropower will remain a part of the state’s “combo platter” energy mix.

Power plant generators have raised concerns about state mandates for hydro and wind, arguing that they will stifle competition and ultimately drive up regional energy costs.

Many power generators — such as the Salem Harbor Footprint power plant that’s scheduled to come online soon — have replaced coal and oil with natural gas.

Environmentalists are concerned about deepening the state’s dependence on gas, a fossil fuel that contributes to greenhouse gas emissions linked to climate change. They’ve fought efforts to build new natural gas lines to the region, which ISO New England argues are needed to ensure a reliable supply of electricity.

“It’s good that coal is gone, but gas is still a dirty fossil fuel,” said Jeff Brooks, an activist who fought for years to shutdown the Salem power plant. “We need to focus our investments on renewable energy.”

Steve Dodge, executive director of the Massachusetts Petroleum Council, said as the state adopts more clean energy policies, natural gas should be part of the equation.

“Natural gas used to be the fair-haired child of environmental community,” he said. “Now we’re considered part of the evil empire, even though it’s one of the sole factors behind the reduction in greenhouse gases in New England.”

To be sure, the state needs to meet benchmarks to reduce its carbon footprint by 25 percent of 1990s levels within three years, and 80 percent by 2050, to comply with the Global Warming Solutions Act, a federal law the state signed onto years ago.

Last year, the state Supreme Judicial Court ruled that Massachusetts isn’t following that mandate and other laws aimed at reducing those emissions. It required annual limits on greenhouse gas emissions until the state meets the environmental goals.

Meanwhile, President Donald Trump’s pledges to roll back environmental protections and rebuild the nation’s coal industry has worried renewable energy supporters about the progress made to make solar and wind competitive against coal and natural gas.

On Thursday, Trump announced that he was pulling the U.S. out of the landmark Paris Accord. The pact, which went into effect Nov. 4, commits countries to action to curb a rise in global temperatures that is melting glaciers, rising sea levels and shifting rainfall patterns.

Trump cited the impact of the agreement on the nation’s coal workers, in part, as one of the reasons for pulling out. He wants to renegotiate terms of the pact.

The move drew immediate condemnation from the state’s environmental groups and political leaders, including Gov. Baker.

Greg Cunningham, a senior attorney at the Conservation Law Foundation in Boston, said the Trump administration’s push to revive coal just doesn’t jibe with the reality of the nation’s energy markets.

“Dirty coal isn’t making a comeback,” he said. “The tide has come and gone.”

Christian M. Wade covers the Massachusetts Statehouse for North of Boston Media Group’s newspapers and websites. Email him at cwade@cnhi.com.